By: Shelby Gatewood, first-year undergraduate at The University of Alabama

Editor’s Note: This post is the fifth of a six-part series highlighting innovative special collections pedagogy. Read an interview with Sarah Smiley’s instructor, Brooke Champagne and review the assignment. Then learn about Mary Dees, Jean Harlow’s stand-in. Sarah Smiley shares her research process to help fellow students understand the fun as well as the challenge of working in the archive. As Champagne taught two sections of the same course,this post features Shelby Gatewood’s essay, which was the chosen piece from Champagne’s second section. An interview with Gatewood will conclude the series on Monday, January 6.

***

The Neglected History of Bryce Hospital

With two days left in the first decade of the new century, the clouds loomed overhead in preparation for the unavoidable rainy afternoon that was to coincide with the meeting of the Alabama Department of Mental Health Advisory Board of Trustees, an unnecessarily long title for a group of members that was to decide the future of Bryce Hospital. The year 2009 marked the official end of the nation’s most recent recession as well as the inauguration of the country’s first African American president. This was a year of change, and the city of Tuscaloosa, Alabama still had one last decision to make. Members of the board gathered at Governor Bob Riley’s office in the capital city of Montgomery to begin the scheduled meeting at 1 p.m (Beyerle, n.pag.)

This was not the first time in recent weeks that Bryce’s future had been discussed. The University of Alabama previously offered to buy the property in early October, but a total offer of 60 million dollars was apparently not enough to satisfy the needs of the state mental health department. The unwavering demand was 84 million dollars. While the university scrambled to revise its offer, fifty-nine miles away the officials of Birmingham were cleverly brewing their own deal to acquire Bryce Hospital. Amidst the hustle-and-bustle of downtown Birmingham, Carraway Hospital shut its doors in 2008 after filing for bankruptcy. With the search for a new Bryce location, the city of Birmingham jumped at the opportunity to bring employment and patients back to this facility. The city was unable to compete financially with the university and the city of Tuscaloosa, but they were able to offer tax incentives to Bryce as well as a preexisting establishment that was prepared to house patients as soon as a deal was arranged. While Birmingham fought hard for the acquisition of this institution, Tuscaloosa had more support from the city’s officials and citizens, 150 years of history with Bryce Hospital, and quite frankly, more money from the university (Beyerle, n.pag.)

Days prior to the meeting, the state passed an amendment that allowed funds from bonds to be used for “economic development.” This vague term presented the state government with the opportunity to use some of these funds to pay the other 22 million dollars needed by the university (the anticipated price was lowered from 84 million to 82 million dollars). With the state’s agreement to cover the University of Alabama’s remaining funds, there appeared to be no question as to the outcome of this meeting. As expected, the advisory board unanimously approved the university’s proposal to purchase the property (with the help of the state) for a total of 82 million dollars which would be used to help preserve the existing building but mainly to fund the construction of a new facility. Governor Riley announced in his press conference after the meeting that Bryce Hospital would stay in Tuscaloosa, and construction had been approved on the property of the Partlow Development Center a few miles away (Beyerle, n.pag.). This decision marked the last significant change of the year for the city, and with the start of a new decade just around the corner, the mental health community was looking more hopeful than it had in almost forty years. This hopeful feeling also lingered in the atmosphere 150 years earlier with the admission of Bryce’s first patient, a 48-year-old soldier diagnosed with Mania A, but this once-hopeful aura diminished in the twentieth century which eventually led to the removal of thousands of patients and the ultimate relocation of the city’s historic Bryce Hospital (“Publications, Bryce,” n.pag.).

~~~

The date was July 4, 1872. Independence Day. The country was just four years shy from celebrating 100 years of freedom. Patients at the Alabama Insane Hospital (a literal and rather blunt title that was renamed to Bryce Hospital at the turn of the century) would never truly know how independence felt while staying at this institution (“Bryce Hospital,” n.pag.). Fortunately, the patients at the Alabama Insane Hospital (AIH) could rest assured knowing that this hospital provided the most humane treatment that was present at that time. Rather than only celebrating freedom from a country, patients at AIH might be thankful for independence from shackles, chains, straitjackets, and torturous treatments such as trephination, cutting off parts of the skull to release spirits that were causing the mental illness (Beidel). Although maybe an adapted form of independence, humane treatment may have been a reason to appreciate this day.

This new day was dawning in Tuscaloosa, and the patients were waking just before the sun colored the sky. Yet another routine day awaited the patients on this Thursday morning. Part of the humane treatment that patients received required adherence to a fairly strict schedule. Keeping the patients in a routine allowed for them to maintain more self-control (Yanni; Kirkbride; The Meteor). The practice of going to bed and rising early was mirrored by other insane hospitals across the country, so 4:30 a.m. was not too early to begin the day (“Life in the Wards,” 3). Men and women were housed in separate wings that were separated by a four-story central building. Men were housed on the west wing while women resided in the east wing with each wing consisting of three stories and nine different wards, or sleeping areas (“Airing Courts,” 3). Most patients slept in single rooms, but less than half of the patients slept in rooms with four or six beds. Not all patients appreciated this arrangement due to the lack of privacy, but those who were scared to be alone at night or patients who were possibly suicidal benefitted from this style of room (Kirkbride). Even with six beds to a room, patients were still given their own somewhat spacious area. In any case, the bedrooms were only used for sleeping at night at the AIH (interestingly enough, patients could sit in hallways outside of their rooms, but they could not sit on the other side of the door). This was enforced because the use of other rooms and the outside air were encouraged (Yanni).

After awaking before the sunrise, patients would walk down the long, dark hall to the dining rooms that were a part of each ward. The patients were fed healthy food (one lunch meal might have been cooked vegetables and soup) from the kitchen. However, the kitchen was below the dining rooms in a basement, and a system was needed to transport the food to each of these rooms. An intricate system of cars, similar to pulleys, was the solution to move food to these separated rooms while still managing to keep necessary foods hot (Yanni). Breakfast was not mandatory and neither was the prayer service led by Superintendent Peter Bryce, but both averaged a decent attendance (“Life in the Wards,” 3).

On the other hand, being examined by a physician was not optional. Treating patients with respect and giving them freedom to walk outside (with an assistant, of course) was not enough to heal the patients of their illnesses. It was also necessary to administer other forms of treatment. If medication was needed in the morning, it was distributed to the patients when the physicians came around at 10 a.m. One of the most common types of medications given to patients in mental hospitals at this period in time was an opiate, which was used to improve physical pain that occurred as a result of these illnesses (“Life in the Wards,” 3). Another common therapy technique was hydrotherapy (which we continue to use today), another way to attempt to relieve physical pain. If this form of therapy was needed, patients would make their way to the bathing rooms (bath rooms with tubs) with an assistant. The assistants would adjust the temperature of the water, either hot or cold as both were common practices, and the patient would soak in the tub. Once finished, patients would step out of the cast-iron tub onto a small rug, so as not to feel the cold, hard floor under their feet immediately after leaving the tub. All of these treatments were usually completed before lunch (Yanni).

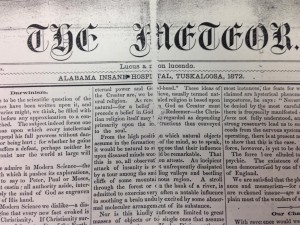

Before the nineteenth century, patients might never have seen the light of day while restrained. However, Peter Bryce believed that patients who were labeled as “insane” could have a positive outcome with proper treatment. One aspect of this treatment allowed the patients to not only see the outdoors for a moment but to experience the fresh air every day while either waiting to be checked by the doctor in the morning or later in the afternoon. Even though assistants were present to watch the patients, they were given the freedom to wander or “stroll” around the property. Patients never seemed to run out of sights to see. The Warrior River flowed just to the north of the hospital, making it easily visible to patients taking their daily walks. Maybe a wander through the woods was a more desirable activity for others. The landscaped lawn gave patients an opportunity to appreciate the beauty of nature. The eye-catching fruit trees provided color throughout the property and perhaps some additional food during the season. These plants also provided patients with the opportunity to pick these fruits during their walks. Plum and peach trees and blackberry bushes were just some of the plants mentioned by a patient in The Meteor, a patient-edited newspaper (“Strolls around the Hospital,” 3). The first edition of this patient-led newspaper was released on this day for ten cents. This edition hoped to familiarize readers with the types of stories that would be published as well as some insider information about the property. While reading The Meteor on this day, patients learned, among other articles, not to expect this paper at a certain time of the year; it would come as a surprise, like a meteor itself (“The Meteor,” 2).

If there was no labor to complete, patients might have taken their copy of The Meteor to the airing court to read. This was an area surrounded by a brick wall that sat behind the wings of the hospital. Most patients usually took advantage of this area with activities other than reading. Men would usually spend this time walking in the court, maybe with accompaniment, or playing games such as cards or even marbles. According to a writer from The Meteor, women were thought to have used this court for gossiping and “practicing the Grecian bend,” a laughable pose in which women bend forward at the waist while simultaneously arching their back. The writer of this article who assumed the frivolity of women, it should be noted, was a man (“Airing Courts of the Hospital,” 3). Other forms of entertainment on the lawn included “playing at croquet” and “jumping the rope” (“Life in the Wards, 3). The freedom to wander throughout the property and play games with others shows the sense of freedom that patients experienced in the Alabama Insane Hospital under Peter Bryce.

Lunch is not well documented, but perhaps it occurred in a similar fashion to breakfast. The afternoon consisted of more leisure time—some patients spent this time outside in the yards or even activities that could have been completed in solitude such as sewing or knitting. There was also an organized “tea time” that was perhaps utilized by patients. Any of these activities were encouraged especially since patients could not use their bedrooms throughout the day (“Life in the Wards,” 3).

Some patients who were employed by the hospital were able to participate in leisurely activities more than others. This component of moral treatment was used to give some patients a sense of responsibility, and Dr. Bryce believed this could help with curing insanity. At this time, around twenty percent of patients were helping with tasks around the establishment—fairly equal numbers of men and women participated. Patients would work anywhere where there was no real threat of danger—such as “the farm, the dairy, the laundry, the sewing room.” Some even worked in the yards and gardens when they were needed. Dr. Bryce employed this method because he believed that this process would help his patients heal (“Labor of the Insane,” 2).

The “early to bed, early to rise” lifestyle ended at night when the patients were finally able to retire to their rooms for a night of rest. This was feasible because of the spacious layout of the beds, the room, and the wards. Imagine, however, being able to hear the person next to you inhale and exhale in his sleep while you lie awake staring blankly at the dark room, wondering what horrible act against humanity that you possibly could have committed that validated your existence in these conditions. You can feel the adjacent patient’s skin grazing against yours due to the lack of space as you ponder the seemingly hopeless future. This is what life at a very different Bryce Hospital was like for Ricky Wyatt in the late 1960s, just over a century after the Alabama Insane Hospital opened.

~~~

Aunt Mildred drove up the familiar driveway to her workplace at Bryce Hospital, but this drive was different. Rather than entering Bryce and proceeding with her duties as a nurse, Mildred was here to admit her fourteen-year-old nephew to the adult mental hospital in town. As a nurse, she witnessed first-hand the grossly inhumane conditions at Bryce, yet she just could not tolerate her nephew’s delinquent behavior anymore. (Apparently back-sassing at school and breaking a few windows qualified as delinquent-enough behavior to ship him to the hellhole that was Bryce Hospital.) And so, with the recommendation from a probation officer, Ricky Wyatt was sentenced to this now morose institution (Davis, n.pag.).

Wyatt was never diagnosed with a mental disorder before or during his time at Bryce, and unfortunately, this seemed customary in the 1960s. Patients could then be thrown into Bryce without a mental disorder diagnosis for reasons such as forgetfulness due to aging or even broken bones. Hence, this overcrowding of 5,000 patients at the hospital became a serious problem. Wyatt and the other non-mentally ill patients were treated like everyone else. Their treatment consisted popping a psychotropic drug (drugs that were developed in the 1960s and used in mental hospitals) with rarely any form of actual therapy. Wyatt described his fellow patients in Ward 19 as delusional, yet they were receiving the same drugs as him, a boy who was nothing more than a delinquent. It seemed easier for the staff at Bryce to simply administer medication to mentally ill patients and “zone them out on meds” rather than actually deal with the symptoms of these disorders. Without proper treatment, patients never became stable enough to leave the hospital—also a factor that led to overcrowding (Davis, n.pag.)

Wyatt disclosed memories in Ward 19 that demonstrate the lack of attention and concern that patients should have received by qualified attendants. Instead, Wyatt remembers attendants encouraging fights between patients, and even gambling on them, simply due to boredom. Wyatt also remembered times in which attendants locked patients away in order to enjoy an undisturbed game or activity (Davis, n.pag.). When Peter Bryce was the superintendent, patients enjoyed the freedom to play games, but with the addition of 5,000 patients, it was now attendants who were enjoying this freedom, and at the patients’ expense. The shortage in number and quality of attendants along with the lack of space created conditions that were “likened to a concentration camp” (Candler, n.pag.). Ricky Wyatt decided that conditions in mental hospitals needed to change, and with the help of Aunt Mildred (who ironically was facing unemployment when there were not even enough staff members to properly run the hospital), Wyatt filed a lawsuit against the Alabama Department of Mental Health, namely Dr. Stonewall Stickney, the Commissioner (Davis, n.pag.)

This historic trial came to a close when the judge ruled that adequate funding for mental health facilities should be funded by the state and claimed that patients were denied their rights when they were treated improperly in these conditions. As a result, Bryce and other hospitals around the state and country took a step in the right direction and began a process of deinstitutionalization—removing patients from hospitals and placing them into smaller, community-like settings (Davis, n.pag.). These smaller hospital institutions were designed to provide better treatment to fewer people in an environment that felt more like a home rather than a prison. Some of these programs were specifically designed to give patients the skills to live successfully in the community (Biedel). A victory for Ricky Wyatt corresponded to a victory for the mental health field.

~~~

From delinquent to hero, Ricky Wyatt served as an example by demonstrating that acquiring knowledge about Bryce Hospital was necessary to bring improvements to the mental health field. Without being forced into the deprived institution, Wyatt would have never have become a pioneer to better the country’s treatment for mental health patients. Rather than resent the state health department for the horrendous conditions to which he was subjected, Wyatt continued to eagerly tell anyone willing to listen about his stay at the hospital. He wanted others to learn the raw history of Bryce Hospital, both the high and low points, so that society could push toward better care for patients. When discussing the university’s plans to turn part of the original Bryce Hospital building into a museum, Wyatt interjected his thoughts about the idea: “Show the different treatments that have been used, good and bad. Show how the patients really lived in the tough times. And they were tough. But show the good side, too. The people who worked hard and tried to do good. There are lots of them” (Davis).

Just as Wyatt became informed about the needs of patients, there needs to be more attention brought to the promising history that the Alabama Insane Hospital faced when it opened as well as the downward spiral that led to conditions that were compared to a “concentration camp” at Bryce Hospital. Progress in the treatment and therapy of patients cannot be made without knowledge of the mistakes that were made around the country in mental hospitals. Only until we learn about the past, can we move to a healthier future.

Works Cited

“Airing Courts of the Hospital.” The Meteor [Tuskaloosa] 30 Mar. 1874: 3. Bryce Hospital Collection. W.S. Hoole Library, The University of Alabama. 25 October 2013.

Beidel, Deborah C., Cynthia M. Bulik, and Melinda A. Stanley. “Abnormal Psychology: Historical and Modern Perspectives.” Abnormal Psychology. 3rd ed. Boston: Pearson Education, 2012. 1-34. Print.

Beidel, Deborah C., Cynthia M. Bulik, and Melinda A. Stanley, “Abnormal Psychology: Legal and Ethical Issues.” Abnormal Psychology. 3rd ed. Boston: Pearson Education, 2012. 531-557. Print.

Beyerle, Dana. “Bryce deal reached.” Tuscaloosanews.com. Tuscaloosa News, 31 Dec. 2009. Web. 15 Nov. 2013.

Beyerle, Dana. “Mental Health board to Discuss Bryce.” Tuscaloosanews.com. Tuscaloosa News, 29 Dec. 2009. Web. 15 Nov. 2013.

“Bryce Hospital.” 1960. Bryce Hospital Collection. W.S. Hoole Library, The University of Alabama. 11 November 2013.

Chandler, Kim. “Bryce will be sold to UA, New Hospital to be built in Tuscaloosa.” Newsbank.com. Birmingham News, 31 Dec. 2009. Web. 15 Nov. 2013.

Davis, Paul. “Wyatt v. Stickney: Did We Get It Right This Time?.” Law and Psychology Review 35 (2011): 143-165. Web. 6 Dec. 2013.

Kirkbride, Thomas S., M.D. On the Construction, Organization and General Arrangements of Hospitals for the Insane. Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston, 1854. Bryce Hospital Collection. W.S. Hoole Library, The University of Alabama. 25 October 2013.

“Labor of the Insane.” The Meteor [Tuskaloosa] 1 Oct. 1872: 2. Bryce Hospital Collection. W.S. Hoole Library, The University of Alabama. 25 October 2013.

“Life in the Wards.” The Meteor [Tuskaloosa] July 1874: 3. Bryce Hospital Collection. W.S. Hoole Library, The University of Alabama. 25 October 2013.

“The Meteor.” The Meteor [Tuskaloosa] 4 July 1872: 2. Bryce Hospital Collection. W.S. Hoole Library, The University of Alabama. 25 October 2013.

Publications, Bryce. Bryce Hospital Collection. W.S. Hoole Library, The University of Alabama. November 11, 2013.

“Strolls around the Hospital.” The Meteor [Tuskaloosa] 30 Mar. 1874: 3. Bryce Hospital Collection. W.S. Hoole Library, The University of Alabama. 25 October 2013.

Yanni, Carla. “The Linear Plan for Insane Asylums in the United States before 1866.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 62.1 (2003): 24-49. JSTOR. Web. 16 Nov. 2013.

2 Responses to Pedagogy Series: The Neglected History of Bryce Hospital